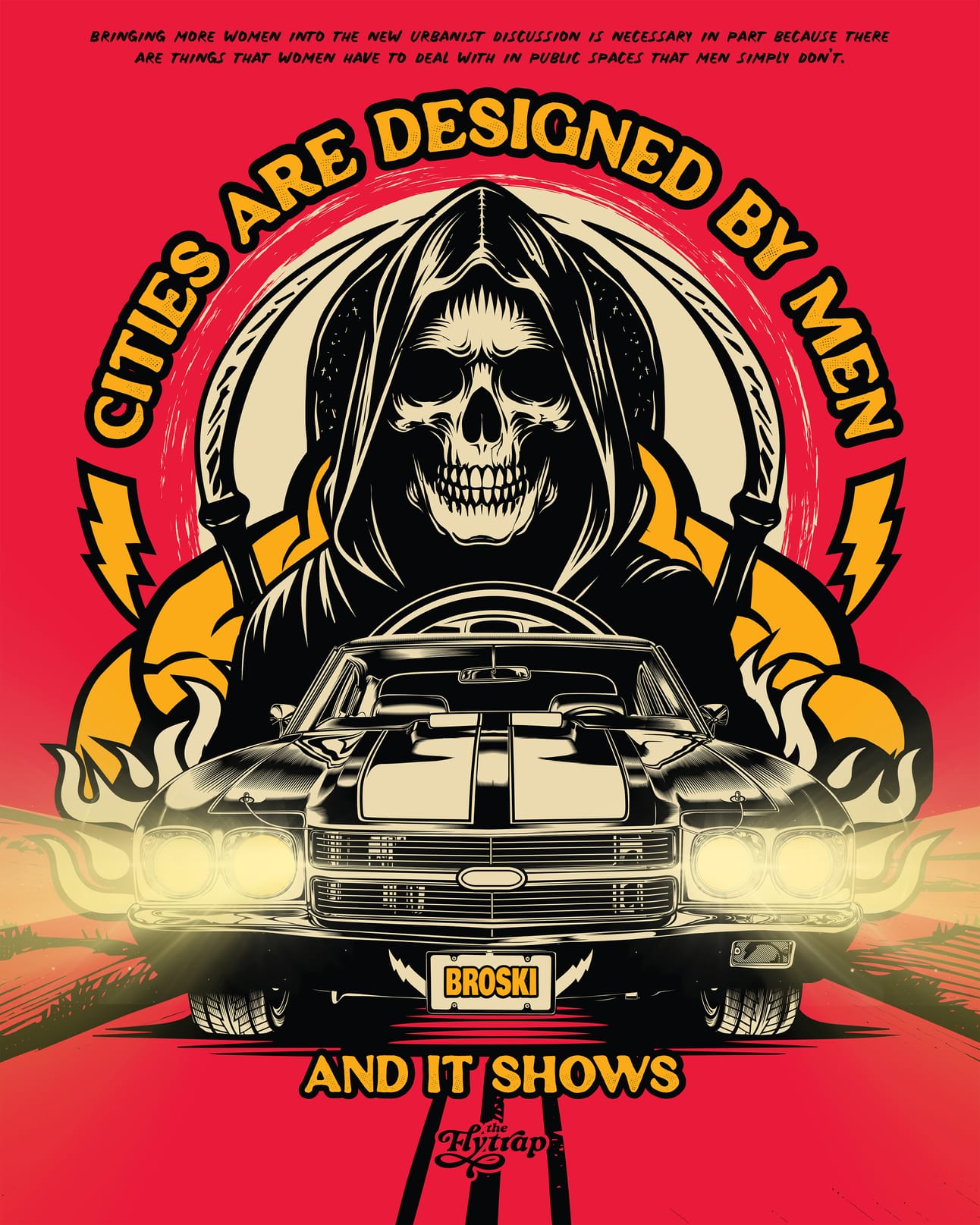

Cities Are Designed By Men – and it Shows

Urbanism is full of critical feminist issues, but the lack of women helping to shape American cities endangers us all.

The Flytrap is a Bookshop.org affiliate. If you buy a book we mention or recommend in the post below, we may earn a small commission.

I am a new urbanist, and I am tired of men.

Men are on television and computer screens, asking me to subscribe as they tell me how we can improve our cities and transit. Men are online, telling me about the 15-minute city. Men are in my city council meetings, telling me we need another lane on that busy road: “Just trust me bro, just one more lane.”

Don’t get me wrong, I love the new urbanist men who have taught me about how much better our cities, roads, and transit systems can be. On YouTube, CityNerd blends snark and – well, nerdy detail on all things cities. There’s Not Just Bikes, who I initially liked a lot but who sometimes comes off as elitist because he had the resources to move to the Netherlands. Or RMTransit, who just announced that he and his comprehensive breakdowns of the world’s train system are leaving YouTube for family reasons.

There’s also Charles Marohn, who founded the group Strong Towns and whose first book, Confessions of a Recovering Engineer, details the urban design failure that led to the death of a pedestrian mother and young child in Springfield, Massachusetts as the family walked to the local library. I like these men; I just find myself hungering for more women in the new urbanist influencer space.

Having more women in the new urbanist space will help ensure safe, reliable transit options not just between home and work, but to the third spaces that are critical to maintaining life. Beyond public transit, we also need well-lit pedestrian walkways and corner design that makes crossing the street safer for women and children alike. While many people mourn any possibility of city streets that are safe for children to walk or adults to bike to work, that life is still possible with good urban planning.

Bringing more women into the new urbanist discussion is necessary in part because there are things that women have to deal with in public spaces that men simply don’t. Do you know why pedestrian bridges are safer for women than pedestrian tunnels? A woman instinctively knows that an underground walking path creates a confined, ill-lit space where her cries for help might be stifled. A bridge does the opposite.

For too long, roads have been viewed strictly through the lens of automobile use, to the exclusion of all others – and this impacts women’s lives significantly.

“What was she doing walking there at that time of day?” newscasters would say, if I was murdered on some dark path at 4:30 in the afternoon on a chilly New England day after the sun had gone down.

The ironic part is, I would also be blamed for my own death if a car struck me while I was crossing the street. Have you ever noticed that when a driver brutally mows down a pedestrian in a half-ton vehicle, newspapers use the same passive voice they use when a cop shoots an unarmed person?

Last week, a driver in New Orleans executed an attack by plowing a Ford F-150 through police barricades into a crowd on Bourbon Street. Before it was clear it was a terror attack, local newspapers used passive voice to describe the scene: “Pedestrians were struck in an accident” or “people hurt in truck-related accident.”

In a world of cars, women are most often the ones tasked with getting things done. In addition to commutes, on average women do more grocery shopping, more retail shopping, and more transportation of children than men. Urbanism is the study of city, road, and transit design. These are all critical feminist issues, but the architecture industry is dominated by men. Sixty-two percent of architects are white men, according to a recent survey of the field. City planning is dominated by men; only 31% of city planners are women. Transit systems are run by men. So too is the new urbanism influencer space.

For too long, roads have been viewed strictly through the lens of automobile use, to the exclusion of all others – and this impacts women’s lives significantly.

I can still remember the last time I used public transit after 10 p.m. It was 2019, and I was on my way home from hanging out with friends. At 11:30 p.m., I rode the red line on the Washington, D.C. Metro. A man I did not know approached me and started talking. Not wanting to be rude, I did the polite smile with short, curt answers to signal that I was not interested in engaging. When my stop arrived, I quickly got off the train. I thought I was in the clear, but about a block and a half away, I noticed that the man was following me home.

Thankfully at the time the local pharmacy was open until midnight, and had exits onto two different streets. I took a gamble, figuring he wouldn’t follow me into the store. I entered onto one street and exited onto another. I lost him, thank God. After that, I got rides from friends or shared an Uber home with a friend, but never again took the Metro.

According to the urban development organization Local Governments for Sustainability, women are the majority of public transport users worldwide, yet their inputs are not considered – and public transit is full of dangers for women. But so too is walking, especially when you consider street harassment, our country’s unwalkable cities, and our largely pedestrian-unfriendly society.

It’s worth noting that, on average, women are smaller than men, and automobile sizes in the U.S. are increasing every year. This makes women pedestrians more at risk for experiencing serious injuries if hit by a car – even as statistics show that male pedestrians are more likely to die of a pedestrian accident (because there are more male pedestrians in general).

The reality of being a woman under today’s city planning regime is that sometimes driving to and fro is the only safe option.

Cities are a reflection of the societies that build them, and these societies include women. The earliest cities were never designed for cars. Indeed, the earliest city designs in ancient Mesopotamia largely featured the very same square blocks we see in Manhattan today because this layout makes it easiest to walk from place to place.

The reality of being a woman under today’s city planning regime is that sometimes driving to and fro is the only safe option.

The Romans spread across Southern and Western Europe, stamping out symmetrical square city blocks, again because walking was king. Most U.S. cities were designed in a similar fashion. Square buildings are the easiest to build, and the square block is the easiest to walk from place to place. It wasn’t until the automobile was invented that freeways and massive interchanges became prevalent.

In fact, roads weren’t even paved until the invention of the bicycle. Only the fanciest of neighborhoods would be cobblestone-paved. Sometimes just a thin strip of stone paved the crosswalk of an otherwise muddy and horseshit-filled city street.

There are a handful of black-and-white videos online showing city life before the invention of the automobile, or during the very earliest days of cars. What you see are streetscapes filled with people. Both men and women are out and about, conducting their business, doing their shopping, crossing the street unfettered and only having to worry about the occasional trolley.

The suburban house with a yard, garage, and white picket fence is often held up as the idealized American abode, but the flight to the suburbs and the societal shift towards car dependency had a detrimental effect on American women’s lives. In the post-war period, which was known for “white flight,” hundreds of thousands of white women went from living in cities with ample public transit and a local trolley system that connected from Washington, DC to Bangor, ME, to living in the suburbs. The previously robust transit systems developed in early America were ripped out root and stem and replaced with buses.

What we have now in our cities and large towns just doesn’t work. What’s true for many women is that we would be more inclined to trust a woman who has experienced unsafe public transit – or who was rendered unsafe by bad urban planning – than the average man who is currently doing this work. Changing that would require that the men who run these industries grant us the opportunity to help design the cities that shape our safety and our lives.

This piece was edited by Tina Vasquez and copyedited by Chrissy Stroop.